Why Does Rousseay Argue That Arts and Science or Philosphy and Culture Have Damaged Morals

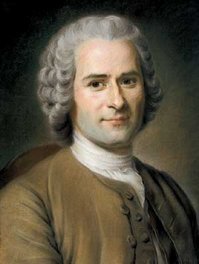

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712—1778)

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was one of the most influential thinkers during the Enlightenment in eighteenth century Europe. His beginning major philosophical work, A Soapbox on the Sciences and Arts, was the winning response to an essay competition conducted past the Academy of Dijon in 1750. In this work, Rousseau argues that the progression of the sciences and arts has caused the abuse of virtue and morality. This discourse won Rousseau fame and recognition, and it laid much of the philosophical groundwork for a second, longer work, The Discourse on the Origin of Inequality. The second discourse did not win the Academy's prize, but like the offset, it was widely read and further solidified Rousseau's place as a significant intellectual effigy. The central claim of the piece of work is that human beings are basically adept past nature, but were corrupted by the complex historical events that resulted in present day civil order.Rousseau's praise of nature is a theme that continues throughout his later works equally well, the about significant of which include his comprehensive piece of work on the philosophy of education, the Emile, and his major work on political philosophy, The Social Contract: both published in 1762. These works caused corking controversy in France and were immediately banned by Paris regime. Rousseau fled France and settled in Switzerland, only he continued to detect difficulties with regime and quarrel with friends. The end of Rousseau'south life was marked in big part by his growing paranoia and his continued attempts to justify his life and his piece of work. This is peculiarly axiomatic in his later on books, The Confessions, The Reveries of the Solitary Walker, and Rousseau: Judge of Jean-Jacques.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was one of the most influential thinkers during the Enlightenment in eighteenth century Europe. His beginning major philosophical work, A Soapbox on the Sciences and Arts, was the winning response to an essay competition conducted past the Academy of Dijon in 1750. In this work, Rousseau argues that the progression of the sciences and arts has caused the abuse of virtue and morality. This discourse won Rousseau fame and recognition, and it laid much of the philosophical groundwork for a second, longer work, The Discourse on the Origin of Inequality. The second discourse did not win the Academy's prize, but like the offset, it was widely read and further solidified Rousseau's place as a significant intellectual effigy. The central claim of the piece of work is that human beings are basically adept past nature, but were corrupted by the complex historical events that resulted in present day civil order.Rousseau's praise of nature is a theme that continues throughout his later works equally well, the about significant of which include his comprehensive piece of work on the philosophy of education, the Emile, and his major work on political philosophy, The Social Contract: both published in 1762. These works caused corking controversy in France and were immediately banned by Paris regime. Rousseau fled France and settled in Switzerland, only he continued to detect difficulties with regime and quarrel with friends. The end of Rousseau'south life was marked in big part by his growing paranoia and his continued attempts to justify his life and his piece of work. This is peculiarly axiomatic in his later on books, The Confessions, The Reveries of the Solitary Walker, and Rousseau: Judge of Jean-Jacques.

Rousseau profoundly influenced Immanuel Kant's work on ethics. His novel Julie or the New Heloise impacted the late eighteenth century's Romantic Naturalism movement, and his political ideals were championed by leaders of the French Revolution.

Table of Contents

- Life

- Traditional Biography

- The Confessions: Rousseau's Autobiography

- Background

- The Beginnings of Modernistic Philosophy and the Enlightenment

- The State of Nature every bit a Foundation for Ideals and Political Philosophy

- The Discourses

- Discourse on the Sciences and Arts

- Discourse on the Origin of Inequality

- Soapbox on Political Economy

- The Social Contract

- Background

- The General Will

- Equality, Liberty, and Sovereignty

- The Emile

- Background

- Education

- Women, Spousal relationship, and Family

- The Profession of Faith of the Savoyard Vicar

- Other Works

- Julie or the New Heloise

- Reveries of the Lone Walker

- Rousseau: Estimate of Jean Jacques

- Historical and Philosophical Influence

- References and Further Reading

- Works by Rousseau

- Works well-nigh Rousseau

1. Life

a. Traditional Biography

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born to Isaac Rousseau and Suzanne Bernard in Geneva on June 28, 1712. His mother died merely a few days after July 7, and his only sibling, an older brother, ran abroad from dwelling house when Rousseau was notwithstanding a child. Rousseau was therefore brought up mainly by his male parent, a clockmaker, with whom at an early age he read ancient Greek and Roman literature such every bit the Lives of Plutarch. His male parent got into a quarrel with a French captain, and at the risk of imprisonment, left Geneva for the remainder of his life. Rousseau stayed behind and was cared for by an uncle who sent him forth with his cousin to written report in the hamlet of Bosey. In 1725, Rousseau was apprenticed to an engraver and began to learn the trade. Although he did not detest the piece of work, he idea his master to be violent and tyrannical. He therefore left Geneva in 1728, and fled to Annecy. Here he met Louise de Warens, who was instrumental in his conversion to Catholicism, which forced him to forfeit his Genevan citizenship (in 1754 he would make a return to Geneva and publicly convert dorsum to Calvanism). Rousseau'due south human relationship to Mme. de Warens lasted for several years and somewhen became romantic. During this time he earned money through secretarial, educational activity, and musical jobs.

In 1742 Rousseau went to Paris to get a musician and composer. Later two years spent serving a mail service at the French Embassy in Venice, he returned in 1745 and met a linen-maid named Therese Levasseur, who would go his lifelong companion (they eventually married in 1768). They had five children together, all of whom were left at the Paris orphanage. It was also during this time that Rousseau became friendly with the philosophers Condillac and Diderot. He worked on several articles on music for Diderot and d'Alembert'southward Encyclopedie. In 1750 he published the Discourse on the Arts and Sciences, a response to the Academy of Dijon's essay competition on the question, "Has the restoration of the sciences and arts tended to purify morals?" This discourse is what originally made Rousseau famous as it won the Academy'southward prize. The work was widely read and was controversial. To some, Rousseau's condemnation of the arts and sciences in the Showtime Soapbox made him an enemy of progress birthday, a view quite at odds with that of the Enlightenment project. Music was nevertheless a major office of Rousseau'due south life at this point, and several years later, his opera, Le Devin du Village (The Village Soothsayer) was a slap-up success and earned him fifty-fifty more recognition. Only Rousseau attempted to live a modest life despite his fame, and afterwards the success of his opera, he promptly gave upwards composing music.

In the autumn of 1753, Rousseau submitted an entry to another essay contest appear by the Academy of Dijon. This time, the question posed was, "What is the origin of inequality amongst men, and is it authorized by the natural law?" Rousseau's response would become the Discourse on the Origin of Inequality Amid Men. Rousseau himself thought this work to be superior to the First Soapbox because the Second Discourse was significantly longer and more philosophically daring. The judges were irritated by its length likewise its bold and unorthodox philosophical claims; they never finished reading information technology. However, Rousseau had already arranged to have information technology published elsewhere and like the Start Discourse, information technology also was also widely read and discussed.

In 1756, a year after the publication of the Second Discourse, Rousseau and Therese Levasseur left Paris after being invited to a house in the state by Mme. D'Epinay, a friend to the philosophes. His stay here lasted but a yr and involved an affair with a adult female named Sophie d'Houdetot, the mistress of his friend Saint-Lambert. In 1757, afterward repeated quarrels with Mme. D'Epinay and her other guests including Diderot, Rousseau moved to lodgings well-nigh the country habitation of the Knuckles of Luxemburg at Montmorency.

It was during this time that Rousseau wrote some of his well-nigh important works. In 1761 he published a novel, Julie or the New Heloise, which was 1 of the best selling of the century. Then, but a yr afterward in 1762, he published two major philosophical treatises: in April his definitive work on political philosophy, The Social Contract, and in May a book detailing his views on educational activity, Emile. Paris authorities condemned both of these books, primarily for claims Rousseau made in them about organized religion, which forced him to abscond France. He settled in Switzerland and in 1764 he began writing his autobiography, his Confessions. A year later, later encountering difficulties with Swiss authorities, he spent time in Berlin and Paris, and eventually moved to England at the invitation of David Hume. However, due to quarrels with Hume, his stay in England lasted only a year, and in 1767 he returned to the southeast of France incognito.

Afterward spending iii years in the southeast, Rousseau returned to Paris in 1770 and copied music for a living. It was during this time that he wrote Rousseau: Judge of Jean-Jacques and the Reveries of the Solitary Walker, which would turn out to be his final works. He died on July 3, 1778. His Confessions were published several years afterwards his death; and his after political writings, in the nineteenth century.

b. The Confessions: Rousseau'southward Autobiography

Rousseau'south own business relationship of his life is given in great detail in his Confessions, the same title that Saint Augustine gave his autobiography over a m years before. Rousseau wrote the Confessions late in his career, and it was not published until after his death. Incidentally, two of his other later works, the "Reveries of the Solitary Walker" and "Rousseau Judge of Jean Jacques" are also autobiographical. What is particularly striking about the Confessions is the almost atoning tone that Rousseau takes at sure points to explain the various public as well as private events in his life, many of which caused swell controversy. Information technology is articulate from this volume that Rousseau saw the Confessions as an opportunity to justify himself against what he perceived as unfair attacks on his grapheme and misunderstandings of his philosophical thought.

His life was filled with conflict, kickoff when he was apprenticed, subsequently in academic circles with other Enlightenment thinkers like Diderot and Voltaire, with Parisian and Swiss authorities and even with David Hume. Although Rousseau discusses these conflicts, and tries to explain his perspective on them, it is not his exclusive goal to justify all of his deportment. He chastises himself and takes responsibleness for many of these events, such as his actress-marital affairs. At other times, however, his paranoia is clearly evident as he discusses his intense feuds with friends and contemporaries. And herein lays the central tension in the Confessions. Rousseau is at the same time trying both to justify his actions to the public then that he might gain its approval, merely also to affirm his own uniqueness equally a critic of that aforementioned public.

2. Background

a. The Beginnings of Modern Philosophy and the Enlightenment

Rousseau'due south major works bridge the mid to late eighteenth century. Every bit such, it is appropriate to consider Rousseau, at least chronologically, every bit an Enlightenment thinker. Yet, there is dispute equally to whether Rousseau'due south idea is all-time characterized as "Enlightenment" or "counter-Enlightenment." The major goal of Enlightenment thinkers was to give a foundation to philosophy that was independent of any item tradition, culture, or religion: i that any rational person would accept. In the realm of science, this project has its roots in the birth of modernistic philosophy, in big part with the seventeenth century philosopher, René Descartes. Descartes was very skeptical about the possibility of discovering final causes, or purposes, in nature. Nonetheless this teleological understanding of the earth was the very cornerstone of Aristotelian metaphysics, which was the established philosophy of the time. And so Descartes' method was to dubiety these ideas, which he claims tin only be understood in a confused way, in favor of ideas that he could conceive clearly and distinctly. In the Meditations, Descartes claims that the material globe is made up of extension in infinite, and this extension is governed by mechanical laws that can be understood in terms of pure mathematics.

b. The Land of Nature as a Foundation for Ethics and Political Philosophy

The scope of modern philosophy was not limited only to problems concerning science and metaphysics. Philosophers of this menstruation also attempted to apply the same type of reasoning to ethics and politics. 1 approach of these philosophers was to depict human beings in the "state of nature." That is, they attempted to strip man beings of all those attributes that they took to exist the results of social conventions. In doing so, they hoped to uncover certain characteristics of human nature that were universal and unchanging. If this could be washed, one could then determine the most effective and legitimate forms of government.

The two virtually famous accounts of the land of nature prior to Rousseau's are those of Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. Hobbes contends that human beings are motivated purely by cocky-involvement, and that the state of nature, which is the land of human beings without civil lodge, is the war of every person against every other. Hobbes does say that while the land of nature may not have existed all over the world at 1 particular time, it is the condition in which humans would be if there were no sovereign. Locke'south account of the state of nature is different in that it is an intellectual exercise to illustrate people's obligations to 1 another. These obligations are articulated in terms of natural rights, including rights to life, liberty and property. Rousseau was also influenced by the modern natural police tradition, which attempted to answer the claiming of skepticism through a systematic arroyo to homo nature that, like Hobbes, emphasized self-interest. Rousseau therefore often refers to the works of Hugo Grotius, Samuel von Pufendorf, Jean Barbeyrac, and Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui. Rousseau would requite his own business relationship of the state of nature in the Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality Among Men, which will be examined beneath.

Too influential were the ethics of classical republicanism, which Rousseau took to be illustrative of virtues. These virtues permit people to escape vanity and an emphasis on superficial values that he thought to be so prevalent in mod society. This is a major theme of the Soapbox on the Sciences and Arts.

three. The Discourses

a. Soapbox on the Sciences and Arts

This is the piece of work that originally won Rousseau fame and recognition. The Academy of Dijon posed the question, "Has the restoration of the sciences and arts tended to purify morals?" Rousseau'southward reply to this question is an emphatic "no." The First Discourse won the university'due south prize as the all-time essay. The piece of work is perhaps the greatest instance of Rousseau equally a "counter-Enlightenment" thinker. For the Enlightenment projection was based on the idea that progress in fields similar the arts and sciences do indeed contribute to the purification of morals on individual, social, and political levels.

The First Discourse begins with a cursory introduction addressing the university to which the piece of work was submitted. Aware that his opinion against the contribution of the arts and sciences to morality could potentially offend his readers, Rousseau claims, "I am non abusing science…I am defending virtue before virtuous men." (First Soapbox, Vol. I, p. 4). In addition to this introduction, the First Discourse is comprised of 2 chief parts.

The first office is largely an historical survey. Using specific examples, Rousseau shows how societies in which the arts and sciences flourished mostly saw the decline of morality and virtue. He notes that it was afterward philosophy and the arts flourished that ancient Egypt fell. Similarly, aboriginal Hellenic republic was once founded on notions of heroic virtue, but after the arts and sciences progressed, it became a social club based on luxury and leisure. The one exception to this, according to Rousseau, was Sparta, which he praises for pushing the artists and scientists from its walls. Sparta is in stark contrast to Athens, which was the eye of proficient gustation, elegance, and philosophy. Interestingly, Rousseau here discusses Socrates, equally one of the few wise Athenians who recognized the corruption that the arts and sciences were bringing almost. Rousseau paraphrases Socrates' famous speech in the Amends. In his address to the court, Socrates says that the artists and philosophers of his twenty-four hour period claim to have noesis of piety, goodness, and virtue, even so they do not really sympathize anything. Rousseau's historical inductions are non express to ancient civilizations, withal, as he as well mentions Prc as a learned civilization that suffers terribly from its vices.

The 2nd part of the First Discourse is an examination of the arts and sciences themselves, and the dangers they bring. First, Rousseau claims that the arts and sciences are born from our vices: "Astronomy was born from superstition; eloquence from ambition, hate, flattery, and falsehood; geometry from avarice, physics from vain curiosity; all, even moral philosophy, from man pride." (Offset Discourse, Vol. I, p. 12). The attack on sciences continues every bit Rousseau articulates how they fail to contribute anything positive to morality. They have time from the activities that are truly of import, such as love of state, friends, and the unfortunate. Philosophical and scientific knowledge of subjects such every bit the relationship of the mind to the torso, the orbit of the planets, and concrete laws that govern particles neglect to genuinely provide any guidance for making people more than virtuous citizens. Rather, Rousseau argues that they create a fake sense of demand for luxury, so that science becomes merely a means for making our lives easier and more pleasurable, just non morally meliorate.

The arts are the subject of similar attacks in the second part of the First Discourse. Artists, Rousseau says, wish kickoff and foremost to be applauded. Their piece of work comes from a sense of wanting to be praised as superior to others. Society begins to emphasize specialized talents rather than virtues such equally courage, generosity, and temperance. This leads to yet another danger: the refuse of military virtue, which is necessary for a society to defend itself against aggressors. And yet, afterward all of these attacks, the First Discourse ends with the praise of some very wise thinkers, among them, Bacon, Descartes, and Newton. These men were carried by their vast genius and were able to avoid corruption. However, Rousseau says, they are exceptions; and the smashing bulk of people ought to focus their energies on improving their characters, rather than advancing the ideals of the Enlightenment in the arts and sciences.

b. Discourse on the Origin of Inequality

The 2d Discourse, similar the start, was a response to a question put forth by the academy of Dijon: "What is the origin of inequality among men; and is it authorized by the natural law?" Rousseau'south response to this question, the Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, is significantly unlike from the Start Discourse for several reasons. Offset, in terms of the university's response, the 2nd Soapbox was not almost equally well received. It exceeded the desired length, information technology was 4 times the length of the outset, and made very assuming philosophical claims; unlike the Offset Discourse, it did not win the prize. Nonetheless, as Rousseau was now a well-known and respected writer, he was able to have information technology published independently. Secondly, if the Start Discourse is indicative of Rousseau as a "counter-Enlightenment" thinker, the Second Discourse, by contrast, can rightly be considered to be representative of Enlightenment thought. This is primarily because Rousseau, like Hobbes, attacks the classical notion of human beings as naturally social. Finally, in terms of its influence, the Second Discourse is at present much more widely read, and is more representative of Rousseau'southward general philosophical outlook. In the Confessions, Rousseau writes that he himself sees the Second Soapbox as far superior to the get-go.

The Soapbox on the Origin of Inequality is divided into 4 primary parts: a dedication to the Republic of Geneva, a brusque preface, a showtime office, and a 2d part. The telescopic of Rousseau'due south project is non significantly unlike from that of Hobbes in the Leviathan or Locke in the Second Treatise on Government. Like them, Rousseau understands order to be an invention, and he attempts to explain the nature of human beings by stripping them of all of the accidental qualities brought about by socialization. Thus, agreement human being nature amounts to agreement what humans are similar in a pure state of nature. This is in stark contrast to the classical view, most notably that of Aristotle, which claims that the state of civil social club is the natural human land. Like Hobbes and Locke, however, it is doubtful that Rousseau meant his readers to understand the pure state of nature that he describes in the 2nd Discourse as a literal historical account. In its opening, he says that it must be denied that men were ever in the pure state of nature, citing revelation as a source which tells us that God directly endowed the first man with understanding (a capacity that he will later say is completely undeveloped in natural homo). All the same, it seems in other parts of the Second Discourse that Rousseau is positing an actual historical business relationship. Some of the stages in the progression from nature to civil social club, Rousseau will argue, are empirically appreciable in and so-called archaic tribes. And then the precise historicity with which one ought to regard Rousseau's state of nature is the affair of some contend.

Function 1 is Rousseau'southward description of human beings in the pure state of nature, uncorrupted by civilization and the socialization procedure. And although this way of examining man nature is consistent with other modernistic thinkers, Rousseau'due south picture of "man in his natural land," is radically different. Hobbes describes each human being in the country of nature every bit being in a constant state of state of war against all others; hence life in the state of nature is lone, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. But Rousseau argues that previous accounts such as Hobbes' accept all failed to really depict humans in the true land of nature. Instead, they take taken civilized homo beings and simply removed laws, authorities, and technology. For humans to be in a constant state of war with one another, they would need to have complex thought processes involving notions of property, calculations nigh the futurity, immediate recognition of all other humans equally potential threats, and possibly even minimal language skills. These faculties, co-ordinate to Rousseau, are not natural, simply rather, they develop historically. In contrast to Hobbes, Rousseau describes natural homo equally isolated, timid, peaceful, mute, and without the foresight to worry about what the future will bring.

Purely natural human being beings are fundamentally different from the egoistic Hobbesian view in another sense too. Rousseau acknowledges that self-preservation is one principle of motivation for human being actions, but unlike Hobbes, it is not the only principle. If it were, Rousseau claims that humans would exist nothing more monsters. Therefore, Rousseau concludes that self-preservation, or more mostly cocky-interest, is only one of two principles of the human soul. The second principle is compassion; information technology is "an innate repugnance to see his fellow endure." (2nd Soapbox, Vol. 2, p. 36). Information technology may seem that Rousseau'south depiction of natural homo beings is i that makes them no dissimilar from other animals. However, Rousseau says that dissimilar all other creatures, humans are free agents. They have reason, although in the state of nature it is non all the same developed. Simply information technology is this faculty that makes the long transition from the land of nature to the state of civilized society possible. He claims that if one examines whatsoever other species over the course of a thousand years, they will not have avant-garde significantly. Humans can develop when circumstances arise that trigger the use of reason.

Rousseau'south praise of humans in the land of nature is mayhap one of the most misunderstood ideas in his philosophy. Although the human beingness is naturally good and the "noble savage" is costless from the vices that plague humans in ceremonious social club, Rousseau is not simply saying that humans in nature are expert and humans in civil gild are bad. Furthermore, he is not advocating a return to the state of nature, though some commentators, even his contemporaries such as Voltaire, have attributed such a view to him. Human beings in the land of nature are amoral creatures, neither virtuous nor vicious. After humans leave the state of nature, they can relish a college grade of goodness, moral goodness, which Rousseau articulates nearly explicitly in the Social Contract.

Having described the pure land of nature in the first part of the Second Discourse, Rousseau's task in the second part is to explicate the complex series of historical events that moved humans from this state to the state of present day ceremonious society. Although they are not stated explicitly, Rousseau sees this development as occurring in a series of stages. From the pure state of nature, humans brainstorm to organize into temporary groups for the purposes of specific tasks like hunting an animal. Very basic language in the class of grunts and gestures comes to be used in these groups. Nevertheless, the groups last only equally long as the task takes to be completed, then they dissolve as speedily equally they came together. The next stage involves more permanent social relationships including the traditional family unit, from which arises conjugal and paternal love. Bones conceptions of property and feelings of pride and competition develop in this phase too. However, at this stage they are not adult to the point that they cause the pain and inequality that they practise in present day society. If humans could have remained in this state, they would take been happy for the about part, primarily because the diverse tasks that they engaged in could all be done by each individual. The next stage in the historical evolution occurs when the arts of agriculture and metallurgy are discovered. Because these tasks required a division of labor, some people were better suited to certain types of physical labor, others to making tools, and still others to governing and organizing workers. Before long, there become distinct social classes and strict notions of property, creating conflict and ultimately a country of war not unlike the i that Hobbes describes. Those who accept the most to lose call on the others to come up together under a social contract for the protection of all. But Rousseau claims that the contract is specious, and that it was no more than than a manner for those in power to keep their power by convincing those with less that information technology was in their interest to accept the situation. And so, Rousseau says, "All ran to run into their chains thinking they secured their freedom, for although they had plenty reason to feel the advantages of political establishment, they did not have enough experience to foresee its dangers." (Second Soapbox, Vol. Ii, p. 54).

The Discourse on the Origin of Inequality remains one of Rousseau'due south nigh famous works, and lays the foundation for much of his political thought as it is expressed in the Discourse on Political Economy and Social Contract. Ultimately, the piece of work is based on the idea that by nature, humans are essentially peaceful, content, and equal. It is the socialization process that has produced inequality, competition, and the egoistic mentality.

c. Discourse on Political Economy

The Discourse on Political Economy originally appeared in Diderot and d'Alembert'southward Encyclopedia. In terms of its content the piece of work seems to be, in many ways, a precursor to the Social Contract, which would announced in 1762. And whereas the Discourse on the Sciences and Arts and the Discourse on the Origin of Inequality look back on history and condemn what Rousseau sees as the lack of morality and justice in his ain present day society, this work is much more constructive. That is, the Discourse on Political Economy explains what he takes to exist a legitimate political regime.

The work is perhaps most significant because it is here that Rousseau introduces the concept of the "general volition," a major aspect of his political thought which is further developed in the Social Contract. There is debate amid scholars about how exactly one ought to interpret this concept, but essentially, ane can understand the general will in terms of an analogy. A political society is similar a human body. A body is a unified entity though information technology has various parts that have particular functions. And merely equally the body has a will that looks afterwards the well-existence of the whole, a political state also has a will which looks to its general well-beingness. The major conflict in political philosophy occurs when the general will is at odds with i or more of the individual wills of its citizens.

With the conflict between the general and individual wills in mind, Rousseau articulates three maxims which supply the basis for a politically virtuous land: (1) Follow the general will in every action; (ii) Ensure that every particular volition is in accordance with the general will; and (3) Public needs must be satisfied. Citizens follow these maxims when in that location is a sense of equality among them, and when they develop a genuine respect for police force. This again is in contrast to Hobbes, who says that laws are only followed when people fear penalization. That is, the country must make the penalty for breaking the law so astringent that people practise not run into breaking the law to exist of whatsoever reward to them. Rousseau claims, instead, that when laws are in accord with the general will, skillful citizens will respect and love both the state and their fellow citizens. Therefore, citizens will run into the intrinsic value in the law, fifty-fifty in cases in which it may conflict with their individual wills.

4. The Social Contract

a. Background

The Social Contract is, similar the Discourse on Political Economy, a work that is more philosophically constructive than either of the first 2 Discourses. Furthermore, the language used in the first and 2nd Discourses is crafted in such a way as to make them appealing to the public, whereas the tone of the Social Contract is not most equally eloquent and romantic. Another more than obvious difference is that the Social Contract was not near as well-received; it was immediately banned by Paris authorities. And although the first two Discourses were, at the time of their publication, very popular, they are not philosophically systematic. The Social Contract, by contrast, is quite systematic and outlines how a government could exist in such a way that information technology protects the equality and graphic symbol of its citizens. But although Rousseau's projection is different in scope in the Social Contract than it was in the starting time ii Discourses, it would be a mistake to say that in that location is no philosophical connection between them. For the before works discuss the problems in civil guild as well as the historical progression that has led to them. The Discourse on the Sciences and Arts claims that society has become such that no emphasis is put on the importance of virtue and morality. The Discourse on the Origin of Inequality traces the history of human beings from the pure land of nature through the institution of a specious social contract that results in present twenty-four hours civil society. The Social Contract does not deny any of these criticisms. In fact, chapter one begins with ane of Rousseau's nearly famous quotes, which echoes the claims of his before works: "Man was/is built-in costless; and everywhere he is in chains." (Social Contract, Vol. Four, p. 131). But different the outset two Discourses, the Social Contract looks forrard, and explores the potential for moving from the specious social contract to a legitimate ane.

b. The General Will

The concept of the general will, first introduced in the Discourse on Political Economy, is further developed in the Social Contract although it remains ambiguous and difficult to interpret. The most pressing difficulty that arises is in the tension that seems to be between liberalism and communitarianism. On 1 hand, Rousseau argues that post-obit the general will allows for individual variety and liberty. Simply at the aforementioned time, the full general volition also encourages the well-being of the whole, and therefore tin disharmonize with the particular interests of individuals. This tension has led some to claim that Rousseau'south political thought is hopelessly inconsistent, although others have attempted to resolve the tension in order to discover some blazon of heart ground between the two positions. Despite these difficulties, all the same, there are some aspects of the general volition that Rousseau clearly articulates. Beginning, the general will is directly tied to Sovereignty: simply not Sovereignty merely in the sense of whomever holds power. Simply having power, for Rousseau, is not sufficient for that power to be morally legitimate. True Sovereignty is directed e'er at the public skilful, and the general will, therefore, speaks always infallibly to the benefit of the people. Second, the object of the general volition is always abstract, or for lack of a meliorate term, full general. It tin ready rules, social classes, or even a monarchial government, only it tin can never specify the particular individuals who are subject to the rules, members of the classes, or the rulers in the government. This is in keeping with the idea that the general will speaks to the good of the society as a whole. It is not to be confused with the collection of individual wills which would put their own needs, or the needs of particular factions, above those of the general public. This leads to a related point. Rousseau argues that there is an important distinction to be made between the general will and the collection of individual wills: "There is often a nifty deal of divergence between the will of all and the general will. The latter looks only to the common involvement; the former considers private interest and is only a sum of private wills. But have away from these same wills the pluses and minuses that cancel each other out, and the remaining sum of the differences is the general will." (Social Contract, Vol. IV, p. 146). This bespeak tin can be understood in an well-nigh Rawlsian sense, namely that if the citizens were ignorant of the groups to which they would belong, they would inevitably make decisions that would be to the advantage of the society as a whole, and thus be in accord with the full general will.

c. Equality, Liberty, and Sovereignty

One problem that arises in Rousseau's political theory is that the Social Contract purports to exist a legitimate state in one sense because it frees human beings from their chains. Simply if the land is to protect individual liberty, how can this exist reconciled with the notion of the general volition, which looks ever to the welfare of the whole and not to the volition of the private? This criticism, although non unfounded, is also not devastating. To answer information technology, one must return to the concepts of Sovereignty and the general will. True Sovereignty, again, is not merely the volition of those in power, but rather the full general will. Sovereignty does accept the proper potency override the particular will of an private or even the collective volition of a particular group of individuals. Notwithstanding, every bit the general will is infallible, it tin only do and so when intervening volition be to the benefit of the society. To understand this, one must accept note of Rousseau's accent on the equality and freedom of the citizens. Proper intervention on the part of the Sovereign is therefore best understood equally that which secures the freedom and equality of citizens rather than that which limits them. Ultimately, the delicate balance betwixt the supreme potency of the state and the rights of private citizens is based on a social contract that protects society confronting factions and gross differences in wealth and privilege among its members.

five. The Emile

a. Background

The Emile or On Education is essentially a work that details Rousseau's philosophy of didactics. It was originally published merely several months afterwards the Social Contract. Like the Social Contract, the Emile was immediately banned by Paris authorities, which prompted Rousseau to flee French republic. The major point of controversy in the Emile was not in his philosophy of education per se, however. Rather, it was the claims in one part of the book, the Profession of Organized religion of the Savoyard Vicar in which Rousseau argues against traditional views of religion that led to the banning of the volume. The Emile is unique in one sense considering it is written as part novel and role philosophical treatise. Rousseau would use this same grade in some of his later works as well. The book is written in first person, with the narrator as the tutor, and describes his education of a student, Emile, from nascence to adulthood.

b. Education

The basic philosophy of education that Rousseau advocates in the Emile, much like his thought in the first two Discourses, is rooted in the notion that human beings are proficient past nature. The Emile is a big work, which is divided into v Books, and Volume One opens with Rousseau'southward claim that the goal of education should exist to cultivate our natural tendencies. This is not to be dislocated with Rousseau'south praise of the pure state of nature in the Second Discourse. Rousseau is very clear that a return the land of nature in one case homo beings accept go civilized is not possible. Therefore, we should not seek to be noble savages in the literal sense, with no language, no social ties, and an underdeveloped faculty of reason. Rather, Rousseau says, someone who has been properly educated will be engaged in society, but relate to his or her beau citizens in a natural way.

At offset glance, this may seem paradoxical: If human beings are not social past nature, how tin 1 properly speak of more or less natural means of socializing with others? The best reply to this question requires an explanation of what Rousseau calls the two forms of self-love: flirtation-propre and amour de soi. Flirtation de soi is a natural form of cocky-beloved in that it does not depend on others. Rousseau claims that by our nature, each of us has this natural feeling of honey toward ourselves. We naturally wait after our own preservation and interests. By contrast, flirtation-propre is an unnatural self-dear that is substantially relational. That is, it comes most in the ways in which human beings view themselves in comparison to other human beings. Without amour-propre, human beings would scarcely exist able to movement beyond the pure state of nature Rousseau describes in the Discourse on Inequality. Thus, amour-propre can contribute positively to human being freedom and even virtue. Yet, amour-propre is too extremely unsafe considering information technology is and so hands corruptible. Rousseau often describes the dangers of what commentators sometimes refer to as 'inflamed' amour-propre. In its corrupted class, amour-propre is the source of vice and misery, and results in human beings basing their ain self worth on their feeling of superiority over others. While not developed in the pure country of nature, amour-propre is still a fundamental part of human nature. Therefore goal of Emile'south natural education is in big part to continue him from falling into the corrupted form of this blazon of self-love.

Rousseau's philosophy of didactics, therefore, is not geared simply at particular techniques that best ensure that the student will absorb information and concepts. Information technology is amend understood equally a way of ensuring that the pupil's grapheme be developed in such a manner as to have a good for you sense of self-worth and morality. This will permit the pupil to be virtuous fifty-fifty in the unnatural and imperfect social club in which he lives. The character of Emile begins learning important moral lessons from his infancy, thorough childhood, and into early adulthood. His teaching relies on the tutor's abiding supervision. The tutor must even manipulate the surroundings in order to teach sometimes difficult moral lessons virtually humility, chastity, and honesty.

c. Women, Marriage, and Family

Every bit Emile'south is a moral pedagogy, Rousseau discusses in smashing particular how the young pupil is to exist brought up to regard women and sexuality. He introduces the grapheme of Sophie, and explains how her education differs from Emile'south. Hers is non as focused on theoretical matters, as men'due south minds are more suited to that blazon of thinking. Rousseau'southward view on the nature of the relationship between men and women is rooted in the notion that men are stronger and therefore more independent. They depend on women only considering they desire them. By contrast, women both demand and desire men. Sophie is educated in such a way that she will make full what Rousseau takes to exist her natural role equally a wife. She is to be submissive to Emile. And although Rousseau advocates these very specific gender roles, information technology would be a mistake to accept the view that Rousseau regards men every bit simply superior to women. Women have particular talents that men practise non; Rousseau says that women are cleverer than men, and that they excel more in matters of practical reason. These views are continually discussed among both feminist and Rousseau scholars.

d. The Profession of Faith of the Savoyard Vicar

The Profession of Faith of the Savoyard Vicar is part of the fourth Book of the Emile. In his word of how to properly educate a pupil nearly religious matters, the tutor recounts a tale of an Italian who thirty years before was exiled from his town. Disillusioned, the young human being was aided by a priest who explained his own views of religion, nature, and science. Rousseau then writes in the showtime person from the perspective of this young man, and recounts the Vicar's speech.

The priest begins past explaining how, afterwards a scandal in which he broke his vow of celibacy, he was arrested, suspended, and and so dismissed. In his woeful state, the priest began to question all of his previously held ideas. Doubting everything, the priest attempts a Cartesian search for truth by doubting all things that he does not know with absolute certainty. But dissimilar Descartes, the Vicar is unable to come to whatever kind of clear and distinct ideas that could not be doubted. Instead, he follows what he calls the "Inner Light" which provides him with truths and then intimate that he cannot assistance but accept them, even though they may be bailiwick to philosophical difficulties. Among these truths, the Vicar finds that he exists equally a gratis beingness with a free will which is distinct from his body that is non subject to physical, mechanical laws of motion. To the problem of how his immaterial will moves his physical body, the Vicar simply says "I cannot tell, but I perceive that it does so in myself; I volition to do something and I do information technology; I will to move my body and it moves, but if an inanimate body, when at remainder, should begin to movement itself, the thing is incomprehensible and without precedent. The will is known to me in its action, not in its nature." (Emile, p. 282). The discussion is particularly significant in that it marks the virtually comprehensive metaphysical account in Rousseau's thought.

The Profession of Faith too includes the controversial discussion of natural organized religion, which was in large role the reason why Emile was banned. The controversy of this doctrine is the fact that it is categorically opposed to orthodox Christian views, specifically the claim that Christianity is the i true religion. The Vicar claims instead that knowledge of God is establish in the observation of the natural guild and i's place in it. And so, any organized religion that correctly identifies God as the creator and preaches virtue and morality, is true in this sense. Therefore, the Vicar concludes, each denizen should dutifully practise the organized religion of his or her own country so long every bit information technology is in line with the religion, and thus morality, of nature.

half dozen. Other Works

a. Julie or the New Heloise

Julie or the New Heloise remains one of Rousseau's popular works, though it is non a philosophical treatise, only rather a novel. The piece of work tells the story of Julie d'Etange and St. Preux, who were one time lovers. Subsequently, at the invitation of her husband, St. Preux unexpectedly comes back into Julie'south life. Although not a work of philosophy per se, Julie or the New Heloise is however unmistakably Rousseau'southward. The major tenets of his thought are clearly evident; the struggle of the individual against societal norms, emotions versus reason, and the goodness of human nature are all prevalent themes.

b. Reveries of the Lone Walker

Rousseau began writing the Reveries of the Solitary Walker in the fall of 1776. Past this fourth dimension, he had grown increasingly distressed over the condemnation of several of his works, most notably the Emile and the Social Contract. This public rejection, combined with rifts in his personal relationships, left him feeling betrayed and even equally though he was the victim of a great conspiracy. The work is divided into 10 "walks" in which Rousseau reflects on his life, what he sees every bit his contribution to the public expert, and how he and his piece of work have been misunderstood. It is interesting that Rousseau returns to nature, which he had e'er praised throughout his career. One likewise recognizes in this praise the recognition of God as the just creator of nature, a theme then prevalent in the Profession of Faith of the Savoyard Vicar. The Reveries of the Lone Walker, similar many of Rousseau's other works, is part story and part philosophical treatise. The reader sees in it, not only philosophy, merely as well the reflections of the philosopher himself.

c. Rousseau: Judge of Jean Jacques

The most distinctive feature of this late work, often referred to only as the Dialogues, is that it is written in the class of three dialogues. The characters in the dialogues are "Rousseau" and an interlocutor identified simply as a "Frenchman." The subject of these characters' conversations is the author "Jean-Jacques," who is the actual historical Rousseau. This somewhat confusing arrangement serves the purpose of Rousseau judging his own career. The character "Rousseau," therefore, represents Rousseau had he not written his collected works but instead had discovered them as if they were written by someone else. What would he think of this author, represented in the Dialogues as the character "Jean-Jacques?" This self-exam makes ii major claims. First, similar the Reveries, it makes conspicuously evident the fact that Rousseau felt victimized and betrayed, and shows perhaps fifty-fifty more so than the Reveries, Rousseau's growing paranoia. And 2d, the Dialogues represent 1 of the few places that Rousseau claims his work is systematic. He claims that there is a philosophical consistency that runs throughout his works. Whether 1 accepts that such a system is present in Rousseau's philosophy or not is a question that was not only debated during Rousseau'south time, just is also continually discussed amongst gimmicky scholars.

7. Historical and Philosophical Influence

It is hard to overestimate Rousseau's influence, both in the Western philosophical tradition, and historically. Perhaps his greatest directly philosophical influence is on the ethical idea of Immanuel Kant. This may seem puzzling at showtime glance. For Kant, the moral police force is based on rationality, whereas in Rousseau, there is a constant theme of nature and even the emotional faculty of pity described in the Second Discourse. This theme in Rousseau'due south thought is not to be ignored, and information technology would be a mistake to sympathise Rousseau's ethics only every bit a precursor to Kant; certainly Rousseau is unique and significant in his own respect. Simply despite these differences, the influence on Kant is undeniable. The Profession of Organized religion of the Savoyard Vicar is one text in particular that illustrates this influence. The Vicar claims that the correct view of the universe is to come across oneself not at the center of things, only rather on the circumference, with all people realizing that we take a common center. This same notion is expressed in the Rousseau's political theory, particularly in the concept of the general will. In Kant's ideals, one of the major themes is the merits that moral deportment are those that can be universalized. Morality is something dissever from individual happiness: a view that Rousseau undoubtedly expresses as well.

A second major influence is Rousseau's political thought. Not only is he i of the most important figures in the history of political philosophy, later influencing Karl Marx among others, just his works were besides championed past the leaders of the French Revolution. And finally, his philosophy was largely instrumental in the late eighteenth century Romantic Naturalism movement in Europe thanks in big office to Julie or the New Heloise and the Reveries of the Solitary Walker.

Contemporary Rousseau scholarship continues to discuss many of the same issues that were debated in the eighteenth century. The tension in his political thought between individual liberty and totalitarianism continues to be an effect of controversy among scholars. Some other aspect of Rousseau'southward philosophy that has proven to be influential is his view of the family, particularly as information technology pertains to the roles of men and women.

8. References and Further Reading

a. Works by Rousseau

Beneath is a list of Rousseau'south major works in chronological order. The titles are given in the original French likewise as the English translation. Post-obit the title is the year of the work's first publication and, for some works, a brief clarification:

- Discours sur les Sciences et les Arts (Discourse on the Sciences and Arts), 1750.

- Often referred to equally the "Beginning Discourse," this work was a submission to the Academy of Dijon's essay contest, which it won, on the question, "Has the restoration of the sciences and arts tended to purify morals?"

- Le Devin du Village (The Village Soothsayer), 1753.

- Rousseau's opera: it was performed in French republic and widely successful.

- Narcisse ou 50'amant de lui-même (Narcissus or the lover of himself), 1753.

- A play written past Rousseau.

- Lettre sur la musique francaise (Letter of the alphabet on French music), 1753.

- Discours sur l'origine et les fondments de l'inegalite (Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality), 1755.

- Oft referred to equally the "Second Soapbox," this was another submission to an essay contest sponsored by the Academy of Dijon, though unlike the Get-go Discourse, it did not win the prize. The Second Discourse is a response to the question, "What is the Origin of Inequality Amidst Men and is it Authorized past the Natural Law?"

- Discours sur 50'Économie politique (Discourse on Political Economy), 1755.

- Sometimes called the "Third Discourse," this work originally appeared in the Encyclopédie of Diderot and d'Alembert.

- Lettre á d'Alembert sur les Spectacles (Alphabetic character to Alembert on the Theater), 1758.

- Juli ou la Nouvelle Héloïse (Julie or the New Heloise), 1761.

- A novel that was widely read and successful immediately afterwards its publication.

- Du Contract Social (The Social Contract), 1762.

- Rousseau's most comprehensive work on politics.

- Émile ou de l'Éducation (Émile or On Education), 1762.

- Rousseau'south major piece of work on education. It also contains the Profession of Faith of the Savoyard Vicar, which documents Rousseau's views on metaphysics, free will, and his controversial views on natural religion for which the work was banned by Parisian authorities.

- Lettre á Christophe de Beaumont, Archévêque de Paris (Alphabetic character to Christopher de Beaumont, Archbishop of Paris), 1763.

- Lettres écrites de la Montagne (Messages Written from the Mount), 1764.

- Dictionnaire de Musique (Lexicon of Music), 1767.

- Émile et Sophie ou les Solitaires (Émile and Sophie or the Solitaries), 1780.

- A curt sequel to the Émile.

- Considérations sur le gouverment de la Pologne (Considerations on the Government of Poland), 1782.

- Les Confessions (The Confessions), Part I 1782, Office II 1789.

- Rousseau's autobiography.

- Rousseau juge de Jean-Jacques, Dialogues (Rousseau judge of Jean-Jacques, Dialogues), First Dialogue 1780, Complete 1782.

- Les Rêveries du Promeneur Solitaire (Reveries of the Solitary Walker), 1782.

b. Works about Rousseau

The standard original language edition is Ouevres completes de Jean Jacques Rousseau, eds. Bernard Gagnebin and Marcel Raymond, Paris: Gallimard, 1959-1995. The most comprehensive English translation of Rousseau's works is the Collected Writings of Rousseau, serial eds. Roger Masters and Christopher Kelly, Hanover: University Press of New England, 1990-1997. References are given by the title of the work, the volume number (in Roman Numerals), and the page number. The Collected Works exercise non include the Emile. References to this work are from Emile, trans. Barbara Foxley, London: Everyman, 2000. The following is a brief list of widely available secondary texts.

- Cooper, Laurence D. Rousseau and Nature: The Problem of the Good Life. Penn State UP, 1999. Cranston, Maurice. Jean-Jacques: The Early Life and Work of Jean-Jacques, 1712- 1754. University of Chicago Press, 1991.

- Cranston, Maurice. The Noble Fell: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 1754-1762. Academy of Chicago Press, 1991.

- Cranston, Maurice. The Alone Self: Jean-Jacques Rousseau in Exile and Arduousness. Academy of Chicago Press, 1997.

- Paring, N.J.H. Rousseau. Blackwell, 1988.

- Gourevitch, Victor. Rousseau: The 'Discourses' and Other Early Political Writings. Cambridge UP, 1997.

- Gourevitch, Victor. Rousseau: The 'Social Contract' and Other Later Political Writings. Cambridge Upward, 1997.

- Melzer, Arthur. The Natural Goodness of Man: On the Systems of Rousseau'southward Idea. University of Chicago Press, 1990.

- O'Hagan, Timothy. Rousseau. Routledge, 1999.

- Riley, Patrick, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Rousseau. Cambridge UP, 2001.

- Reisert, Joseph. Jean-Jacques Rousseau: A Friend of Virtue. Cornell UP, 2003.

- Rosenblatt, Helena. Rousseau and Geneva. Cambridge: Cabridge Up, 1997.

- Starobinski, Jean. Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Transparency and Obstruction. Chicago: Academy of Chicago Printing, 1988.

- Wokler, Robert. Rousseau. Oxford: Oxford Up, 1995.

- Wokler, Robert, ed. Rousseau and Liberty. Manchester: Manchester Upwardly, 1995.

Neuhouser, Frederick. Rousseau's Theodicy of Cocky-Love: Evil, Rationality, and the Drive for Recognition. Oxford University Press, 2008.

Writer Information

James J. Delaney

Email: jdelaney@niagara.edu

Niagara University

U. S. A.

Source: https://iep.utm.edu/rousseau/

0 Response to "Why Does Rousseay Argue That Arts and Science or Philosphy and Culture Have Damaged Morals"

Post a Comment